THINK OF THE PAY CHEQUE - Our Worst Pay Cheques

Ahead of our live storytelling event next week, the Pantograph Punch's stable of writers take a look at some of their own adventures in bad jobs.

On Thursday the 13th June, the Pantograph Punch is hosting its second live event, Think Of The Pay Cheque: Adventures In Bad Jobs. Shit jobs, or even terrible moments in rewarding jobs, are a social go-to. Talking about them can act as a pressure valve in the heat of the moment, but they’re also a chance to see people’s fears, anxieties, hopes and hates lain bare in a social space virtually everyone has to share at some point. Appropriately, it’s a live storytelling event, and we’ve found the pick of them – Nisha Madhan, Tim Lambourne, Jo Holsted, Matt Nippert, David Slack, Ema Tavola and David Farrier. Presented by Barnie Duncan, it’s also not quite your regular conveyor belt of shame and woe – though you’ll need to see why on the night itself. In advance, we asked each other to come up with our own career lowlights. We also tried to get a couple of people to come and get a bad job working for us. You can see the final result here:

Joe

I’ve felt really lucky to have every job I’ve had – but here’s the one that nearly broke me. I took extra work when a university project was drying up as a ‘work-from-home’ outbound caller for a music-licensing agency. For those who don’t know, the recording industry collects copyright fees from bars, cafes, restaurants, gyms, and pretty much any commercial enterprise that allows members of the public to pass in and out of their premises and plays recorded music to try and lure them in. Though it’s probably a very fair quid pro quo for someone who’s downloading their tunes for free and piping them through their skatewear store, it also applies to nice old ladies’ tearooms in the Hokianga whose proprietors have never seen a computer.

The official-cum-legal rationale is that there a public performance right for these works that was not granted in the sale of the recording itself, and that this is a fair way to recoup it for struggling Kiwi artists. And the critical response is that this revenue wasn’t sought with such co-ordinated, aggressive determination until the recorded music industry was falling over, so it's a sort of ambulance doubling as a collection agency at the bottom of the cliff - and that nearly three-quarters of the fees accumulated are sent overseas, based on calculations that factor in commercial radio play. Meanwhile, this Your Viewsfrom the Herald is a less nuanced but pretty accurate representation of how most people on the street respond to the whole concept. I got to hear from them a lot.

Few people want to hear from cold callers, but you always have the elderly, the lonely, the compassionate, and people who may just really, honest-to-god, want to consider a timeshare or a new life insurance policy. There’s a sliver of humanity, and hope. It’s not the same when you tell a small business owner that it’s time for them to pay a fee that they’ve never heard of, to an organization they had no idea existed. “It’s not a tax.” “I can assure you, we’re the official organization. We sent you a letter.” “It’s not a scam.” “This will help struggling Kiwi musicians succeed.”

I got yelled at by famous people. A former Auckland rugby rep who now runs a pub. One of the city’s most-loved restauranteurs. I got called a crook, a middleman, and a parasite. And they were all absolutely right, because beyond failing to sell my argument to them, it shone through that I couldn’t even sell my argument to myself. I had hit the wall of persuasion, and in this sense it was a good test of my limits. Students can get a pretty smug certainty about their prospects and abilities as they yawn through a cruisy part-time job. I know. I felt it, sometimes. This job, though - this shook my certainty to the core. My own desk, which I worked from, became a thing of dread. I started to hate using the phone at all. To this day, I retain a Stockholm Syndrome-esque fear and favour of angry, sweaty small businessmen on the evening news who refuse to cough up a cent.

I can count the commission fees I earned on one hand. All were from timid Asian women operating small restaurants, most of whom I’m sure thought I was the IRD. If anything, these moments of success made me feel worse. After several weeks of abject failure, I handed in my notice and took a gig tutoring high-schoolers in an semi-abandoned Greenlane house that may have been a money-laundering scheme. In the next year, I would watch The Shawshank Redemption more times than any other human being in Christendom. It felt great.

Jose

This wasn't my worst day on the job, but it was very confusing at the time. I'm still haunted by it; I think I always will be.

This is what happened. Years ago I was on-air reading the morning news at bFM and I pronounced Shi'ite as "Shit-ites." I don't know how I did it. At the time it seemed like the most natural thing in the world and I went back to my desk and sat down. I think I may have even gone downstairs to the Uni quad and bought some five dollar butter chicken (my lifestyle at the time is probably best described as nutritionally embellished) before I realised what I had delivered in my best authoritative news voice. I'd like to make clear that I do know how to pronounce Shi'ite and that I knew how to pronounce it then, and that I do not think the adherents of Shia Islam are made of poos.

To my surprise no one seemed to notice, or, at least, no one contacted the station to complain about the little bastard who had unceremoniously slandered a large denomination of the world's Muslims. There are many things one could extrapolate from that, I choose to believe that my delivery must have been so powerful no one dared correct me. So that happened and the world turned on and I had many more butter chicken curries at 10:15 in the morning.

Matt

I've had several customer-facing roles, which while not exactly terrible sometimes brought to mind that line about the banality of evil. When I was a teenager I worked checkouts. One afternoon I was idly scanning bought items and making small-talk with the customer when I began to notice all of the items I was ringing up were coated in a thin, slimy milky film. I stopped scanning and asked the customer if she knew what had happened. "Yeah," she said, "my baby vomited in the basket." She looked at me. I looked down at my hands, now coated with vomit, and then back at her. "Sorry," she said.

Hayden

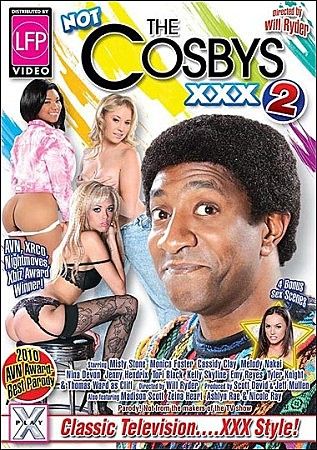

Having never gained experience in retail or hospitality - the stock trades of middle-class youth - I've always had to seek out odd little jobs to get by between larger endeavours. Most have been bland stints filing financial documents or cold calling Australians about their greeting card purchasing habits, but the worst was what at first seemed like any another benign admin job: alphabetising DVD sleeves for an online movie rental company. It shouldn't have been a surprise, but I quickly came to realise a core part of the company's business was porn. Shitloads of porn. Which in itself wasn't the worst thing in the world. But as I worked my way through the A's - Anal Adventures...Anal Adventures II...Ass Bandits... I found a sick trend in the tastes of New Zealand's paid-for HD porn consumers: porno parodies.

I wasn't really aware of their existence until I was confronted with the task of organising endless piles of sleeves for titles like The Sex Files or Quantum Deep. You'd think the prerequisite for a good porno parody would be a solid pun - but the apparent demand for fresh parodies seems to have driven Porn Valley to sausage factory (sorry) levels of creativity, whereby studios slap "This Ain't" or "a XXX Parody" onto any old TV title. The breadth of the genre and the horny hunger of its audience has lead to some studios exploring sublimely absurd territory: This Ain't Curb your Enthusiasm, The Biggest Loser - The XXX Parody, This Ain't Dirty Jobs XXX, Jersey Shore XXX a porn parody, Naporneon Dynamite...

There's something so hypnotic about the methodical repetition involved in alphabetising for eight hours a day that I'd go home each night and mildly hallucinate, finding myself in a poorly acted parody of real life, where each conversation was made up of ABCs and inevitably led to gratuitous sex.

Adam

I spent most of my teens (and then some) working in hospitality, and collected a good number of horror stories: breaking expensive things, accidentally serving people food they were allergic to, getting cleaning fluid in a deep-fryer. But my worst experience as a working stiff was out of the kitchen, as an 'Outbound Call Centre Operator' during the summer of 2009-2010.

For four nights a week and one eight-hour shift on Sundays I was the sworn enemy of people with landlines. I was a cold-caller for Forest & Bird and WWF, an unsolicited intrusion on your dinner who was contractually obliged to harangue you for money. I wasn't even working directly for the charities - the call centre I worked at was a finely-oiled capitalist machine to whom those organisations had outsourced their year-round collection drives. Internal targets were all the rage and genuine passion for saving the environment was supplanted by a tired script, a lack of education about what you were actually calling for, and the relentless badgering of the mark. Can't pay twenty dollars? How about ten? Five? How about I call you later this week? No? How about next week? Are you sure you don't want to donate? It's for the dolphins.

This doesn't even touch on the best thing about the job, though - the personal abuse. It's easy to see cold-callers as unfeeling drones, calling up to suck hard-earned money out of your wallets without so much as a how do you do. A lot of people do. A lot of people will take the time out of the busy day that you've interrupted to call you 'asshole', 'cunt', 'dick' and a 'communist'. One person aggressively challenged me about Forest & Bird's 1080 policies, catching me in a fifteen-minute rant I didn't have the knowledge to fight or the energy to escape. Cold-calling for charities is definitely not the worst job ever, but it can still be a thankless, soul-crushing experience, its philanthropic aims crushed under ruthless performance goals and the vitriol of those you call.

Oh, I forgot to mention the handful of times when I called a number and asked for someone only to find out that they had recently died. That was fun.

Rosabel

I discovered contract jobs in my first year of university. It was wonderful. The work was varied enough to suit my short attention span and paid unsurprisingly well. I spent weekends flitting around the greater Auckland region: Supervised an afterschool class of Korean children. Didn't speak Korean. Didn't seem to matter. I mystery shopped. To make it interesting, I created characters for myself. 'Regular person at the mall' was a favourite. I bought shoes, had my hair cut, ate cakes, sent mail. On occasion I wondered if I was the one being mystery shopped. "Didn't buy the promotional candybars," I imagined the guy at the petrol station whispering into a hidden microphone. For a month I collected census forms. For two months I ghost-wrote the autobiography of a shuttle bus driver. For a year I tutored high-achieving teens in English and Maths. Mostly this involved nodding encouragingly as they finished their homework in silence.

And then, of course, the inevitable: door-to-door market research.

When you spend your weekends being asked to get off people's properties, you learn resilience. Don't have time right now? I can come back at a time that suits you! No time suits you? Hey, we're busy people! Oh you're closing the door in my face, okay, have a nice day!

After the first few weeks I began greeting strangers with the injured expression of the emotionally abused. It wasn’t conscious. I developed a slight upward lilt at the end of each sentence, a reflexive flinch the moment I delivered my spiel. The days were long. They were mostly miserable. But people were inviting me in. The secret, it turns out, is not confidence. It’s pity.

Harnessing my unhappiness made the job easier. And it was straightforward enough - asking people about their favourite radio stations, how often they drank a certain brand of soda. My boss was impressed. "We're assigning you to a new project," she announced one day. The new project: asking people about their intentions to write a will. It was a long survey, I was told, and would take around 45 minutes in total. There were a lot of questions. The ones about the will were couched in general ones about the client, and the values they needed to project in order to market themselves effectively. I spent weekend after weekend on musty floral couches, asking men and women I'd never met to face the possibility of their death. What would motivate them to do something about it? How about... a company with integrity? How about... one with reliability? It felt intrusive and incredibly macabre. Nobody else seemed to mind. “I’m going to have a cardboard coffin,” one woman told me. Another detailed the complexity of her relationship with her son. I remember surveying one woman in a retirement village. It was afternoon and she kept the curtains drawn, and at the end of the session I handed her an envelope containing two movie tickets – it was their reimbursement for completing the survey. “No, I don’t want these,” she told me, handing them back. She seemed disappointed with me. With my thoughtlessness. “It'd be a terrible waste of my time.”

Bronwyn

During a particularly poverty stricken time of my first year of university I hadn’t quite learnt that any job that promises “variety”, “opportunity to travel”, is looking for a “bubbly people person” and is happy to employ someone for $16/hour on the basis of a five minute phone interview that essentially assessed the likelihood of that person to abscond with 160 bottles of Boost effervescent energy drink tablets is unlikely to be a great long term employment prospect. Hence my glorious career as a supermarket demonstrator began.

On site at Newtown New World, my job was to stand about the bulk food bins, divide each large tablet into quarters, place one quarter into a plastic shot glass, and tempt people into trying one. When the shopper approached, I would, like the most punch-worthy mixologist you’ve ever seen, pour water into the glass to demonstrate the incredible effervescent powers of Boost. It was exactly as tedious as you could imagine, especially after the first three hours of an eight hour shift. However, the dullness of repetitively quartering tablets, filling the water jug, and smiling like a cheshire cat, was interrupted by that most bemusing of entities: the public.

Approximately every one in three person who was game for a Boost would say “Will this sort out my hangover? Haha.”; another third would angrily declare it to not be as good as their usual effervescent energy drink of choice, and the rest of the people were either distracted, grumpy, or very, very, happy to be able to talk with someone who was contractually obliged to not inch away from them. The most notable of these was a slightly older man who chatted about the weather, the rugby, the character of Newtown, and then asked in a variety of ways what time I finished, where I would be going when I finished, and if I didn’t have any other plans, would I like to come around and watch Shortland Street with him and a bowel of popcorn? At the end of three very long days and several visits from my Shortland Street loving friend, I had twenty-three tubes of Boost left; unable to be returned, my supervisor said I could keep these as a bonus: “They might help with those hangovers around the flat. Hahaha”.

Uther

I have lots of shit work stories but the dread tyranny of perspective and distance usually, on repeat viewing, tends to throw my past self’s flaws into sharper relief than those of the actual job. As a white, creative, middle class child of privilege, I have to admit that I’ve spent a lot of my life feeling and certainly acting like work was an annoying distraction, an obstacle in the way of the real work: doing whatever the fuck I want.

Then I was unemployed for a year. A full year. And it sucked.

I will admit that the first month, maybe the first two months. It was kind of awesome. I sat at home. Watched the whole of The X Files and then Frasier. I kept making lists of all the great changes I was going to make to my life tomorrow (I still make those lists) and then tomorrow would could come and the day after that seemed like a much better day to start and so on. It wasn’t great but it didn’t hurt. At first that is.

After the tenth failed job interview, you hate the people who aren’t giving you jobs.

After the twentieth, you hate the world.

After the thirtieth, you hate yourself.

I interviewed for over fifty jobs in that year. It just wasn’t happening for me. McDonald’s told me I was overqualified with my NCEA level 3. The men at Dick Smith laughed in my face when I didn’t know the answer to an oddly specific question about component video cables. WINZ put me through a series of increasingly bizarre courses which climaxed with a man who kept insisting that he had discovered Fur Patrol watching over me do a test that involved assigning the correct emotions to situations like ‘Buying milk from Mr. Patel,’‘Saying Goodbye to an old friend as they leave for Singapore,’and ‘Standing next to someone on the street.’

My favourite story from that year (that I’m not saving for a play) I usually tell very quickly. It goes like “Have I ever told you about the job I had for a week? I sent in my CV on Monday, Interviewed on Tuesday, Trained on Wednesday, Worked the Thursday and Quit on the Friday.”It was selling stuff door to door and was worse than you assume it to be. Because we sold shit. A key ring digital camera that for fifty dollars would sit out ugly VGA bitmaps. An molting singing cat doll. Things like that. It was, the more I think about it, a lot like a cult. They were obsessed with “Your numbers” If you weren’t getting a lot of sales, it wasn’t your fault, it was just Your Numbers for that day.

When I tell this story I tend to focus on the training day where two old hands at it showed me the ropes. They were both younger than me, a sixteen year old hyper go-getter still on the high of Her Numbers being so great the previous week and a seventeen year bottle blonde who kept making the girl with good numbers stop the car so she could vomit out the window. My memory has transformed them into the hilarious comedy duo. The go-getter short and round, the spewer a tall, wobbly stick. Which is a nice detail, but tends to ignore the weird sense of tragedy and unease that hung over the whole day. Turned out that the vomiter was vomiting because she was pregnant. Throughout the day, you often intersected or met up with other sales teams, to share information or just skive off a bit. So I got to watch, over the course of this Wednesday, the spreading of the news of her impending parenthood. And, when her back was turned, the rampant bitching speculation as to who the father was. She got around. Apparently. It could have been anyone.

There are two bits of this story I never tell. One is the bit where really stung by the bitching (of course she heard all of it), I watched the mother-to-be cry, smoke and tell me (and only me) that Darren had to be the father. She’d only ever been with Darren. Darren ran the warehouse. The first time I met him he spent a good ten minutes showing me all the places he’d slept with people around the warehouse. One of those places was on a fully raised forklift. He referred to sex as ‘rabbiting’and nothing else. That is what this place was like.

The second bit I never tell is that I didn’t quit on that Friday. I had my first proper panic attack waiting for the bus on Lambton Quay and just didn’t go. I bought a new sim for my phone so they couldn’t contact me. When I have the 2 a.m fear and start to list all the hideous things I’ve done, this always tops the list. I write this knowing that company closed several months later under suspicious circumstances.

I did, eventually, find a job. That wasn’t like a cult. But that was after I’d already signed up for university. So, in a trend that had happened before and that continues to this day, I went very quickly from looking to the future and seeing nothing but a desolate wasteland to seeing a crowded, stress-generating vortex of stuff I don’t remember agreeing to. But this time when I say there was work there, that wasn’t the part I hated. I had seen what work did to people, I had felt what not working was like. I knew which I preferred.

THINK OF THE PAY CHEQUE

Thursday 13 June| 7.30pm | Auckland Trades Hall, 147 Great North Road

Tickets available from Under The Radar