The House of the Novel

It started one day while I was doing my PhD. Lynn Jenner worked in an office down the hall from mine and when things weren’t going well I would wander down and stand in her doorway, look at what she was reading and we would talk about the particular ways things go wrong in writing.

On this day, let’s say it was Tuesday – not hump-day, not the end of the week, not the horror of a Monday – things were not going well. Things had not been going well for a while. I was writing a novel, something I’d never done successfully before. I’d already written three novels in an attempt to write the one I hoped to submit as part of my PhD. I’d thrown away two of them and was left with the tired, floppy eleventh draft which had pushed me out of my office and down to Lynn’s. It was at an awful stage. I felt like I’d found the scope and the map of the thing but not its shape. I had, as we say in the writing game, a structural problem.

‘It’s not right,’ I whined. Looking out Lynn’s window down at the marae, trying to seem off-hand. ‘It’s another completely unsatisfying draft.’ I’d spent the last week working from beginning to end referring to a list of chapter summaries I’d made that were acting as a plan for the final structure of the novel. I’d read through this latest draft the day before and it wasn’t good, it was flat and there was this aching hole in it that I couldn’t find that seemed the doorway to some better way of telling the thing. As I left the day before, I figured I must have messed up the plan somehow but this morning, this awful, middling, mediocre Tuesday morning, I realised I’d got exactly the structure I’d planned. It was the plan that was wrong, my thinking around how best to tell the story was wrong but now that it was in an order I felt like if I moved any part of it the whole thing would implode and I’d be back with the bits and pieces of story scattered at my feet, or worse – nothing.

It wasn’t good, it was flat and there was this aching hole in it that I couldn’t find that seemed the doorway to some better way of telling the thing.

‘Maybe I’ve worked on it too long,’ I said. ‘Maybe I should start again.’ Starting again is my crack cocaine. This is how I’d ended up with three almost-complete novels when I was only supposed to be writing one. I am an Olympic-qualifying beginner. It’s always the finishing that does me in. Starting again always seems easier to me than revising what I have. In fact, starting again is how I revise. I print out a copy of the last draft, sit it next to me, type it out in a fresh document making changes as I go until eventually I’m not looking at the paper draft at all, I’m writing new words in a new shape and often creating a whole new structure. This had worked and continues to work for me when I’m writing short fiction but with this extended piece of work it all took too long.

I also realised quite early into the novel writing process that what I’d actually been doing with the short fiction was memorising it in a way. I have very little time to sit down in front of a computer and write so I write in my head. I tell myself the story over and over as I walk the dog, as I pick up the child, as I edit technical documents for money. When I’m talking to you over coffee or at a business meeting I’m often thinking, What if my character knows but the reader doesn’t? What if I tell them about the earthquake first? What if it’s two parts rather than lots of chapters? While writing the novel I took the long way to every appointment so I had time to tell myself more of the story but there was no way of holding the whole thing in my head for long or at all. I couldn’t see the shape of it – its structure. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘I think I need to start again. It’s too weak to hold up to any more re-jigging.’

‘Yeah,’ said Lynn. ‘We always think of them as fragile at this stage, eh? It’s almost like at this point we need to think of them as really robust, like we can knock out walls and replace windows and they’ll still stand.’

I’d been writing about buildings. The novel was about engineers. I’d been learning about force – dead loads, live loads, shear, bending and it was in that moment, as Lynn said those words that my novel popped out into three dimensions. Suddenly, instead of poking at its surface, shifting the elements of the novel around like jigsaw pieces or playing cards, I found myself contemplating the idea of walking around inside the thing. Looking at it from the street sure, but then knocking on its door walking into its interior, making a survey of its rooms and, then, some renovation decisions.

‘And if it’s not strong enough,’ Lynn continued, ‘we kind of need to find a way to hold it strong while we do our work.’

Lynn knew about renovations. While she was in Kelburn writing, men were adding a new room to her home. She’d been visiting her mother in Christchurch frequently, often acting as my witness to the destruction after the earthquake then the achingly slow rebuild.

‘Scaffolding,’ she said. ‘Bracing.’

The building metaphor is extremely hard to actualise as allegory. I’ve never pushed it to the point of: element of novel equals part of house, plot equals walls, say, or event equals rooms. But it helped me while I finished that book and it continues to help me as I continue to write new work. At first I remember it was the strength Lynn talked about, the strength I knew a building had, that helped me through that last draft.

Before the conversation I visualised my writing as a game of Jenga. As I removed a block from one part of the tower it affected all the other blocks. Sometimes I could see the effects straight away, sometimes I wouldn’t see the effects until later when there was a collapse. Basic physics shows that an object is most stable when it has a large base and a small height. So for my short stories the Jenga visualisation worked fine – in a short tower it’s easier to move blocks around and if there is a collapse there are less to pick up. However, as my novel Jenga tower got taller and taller I was almost paralysed by fear because the stakes were so much higher for moving one of the blocks. So this was the emotional baggage I was bringing to my revising. This scary tower of blocks which was not working but I was too scared to change. But Lynn was right, my novel didn’t have to be a tower of blocks – it could be a sprawling one-storey estate, or, if it was a tower, it could have high-strength reinforced concrete beams and drilled bell pier foundations that supported any alterations I made.

I started to think about the research I’d done, the multiple drafts and the backstory I’d written as part of this reinforcing strength. If I knocked out a metaphorical wall, I knew what was in the gaping space it left. If I didn’t, there were other parts of the building I could go to which would help me figure out what was in that space. Suddenly my novel didn’t seem ‘too weak for re-jigging’. Instead, it seemed to invite the possibilities of shift and change. It wasn’t a tower of single-sized blocks any more but a puzzle of distinct elements, one of which, I was sure, would fix any structural weakness I created through my revision.

The other useful thing for me about visualising my work as a three-dimensional object I can get inside is that structure transforms from an abstract thing into a very concrete one. A lot of the time I write by feeling. I write the next thing, the thing that seems to call me or that makes the right noise inside me. This works well for creation – that first draft. It also works pretty well for short fiction when I can hear all the noises of the work and its entire emotional landscape in my body right to the last draft. However, I can’t do this with rewriting the novel. I find that by wandering through this house of the novel I can ask questions like, Is this a supporting wall? Does this room need a skylight? Where does it get the afternoon sun? Even something as simple as, What type of building is this novel? which can offer great returns. I also think a lot about the path different characters might take through the house. I think about the path I want the reader to take. I think about where I want to them rest, where I want them to run. Like I say, this is not an easy Plot A equals master bedroom exercise.

The trick for me has been the wandering, the loose grip, the curiosity, the things that I sometimes find in some of the rooms that I don’t remember putting there.

This kind of visualisation often raises more questions than answers and the building is often more House of Leaves than Bridehead Revisited. I can wind myself into knots trying to make this equal that and I would never use this exercise on its own to rewrite a novel but it does have a profound effect on how I interrogate the structure of a longer work. The trick for me has been the wandering, the loose grip, the curiosity, the things that I sometimes find in some of the rooms that I don’t remember putting there.

The thing that I think is most important about this game that I play with myself is that it frees me from words. On that Tuesday, the one with Lynn Jenner and the awful eleventh draft, what I had were lists. To deal with the bigness of the novel I needed to summarise parts of it and I’d used words to do this signifying, symbolic work – in spreadsheets, on notecards, written large on A2 sized mind maps. And these were helpful. I needed to capture my thoughts. However, a lot of the time I fell into the trap of trying to fix the problem using the technology that had caused it. The stakes seem low when I wander my novel house. Words, or the putting of words on paper can be a daunting prospect for me when things are not going well. But this imaginative tour seems to open a different way into the work. I don’t know much about the subconscious but I often wonder if that is what is at play here for me, if it’s almost like dreaming my way into the work. There always seems to be some part of me I can tap that knows exactly what the house looks like. The other freedom I get in this process is the freedom from an implied reader. I’m not communicating my house to anyone except myself, I can use my own language – visual, aural, taste, touch. In this way I free myself from the dominance of the written word in writing. This sounds counter-intuitive but living with a non-lexical nine-year old who loves video games and imaginative play has shown me that there are more ways than writing to tell stories. I started to wonder if it was possible to design a workshop where we dismantled our written stories through the exercise of making them three dimensional and then put them back into words through talking with each other about these imagined and built structures.

So when Kirsten Le Harivel from Kahini emailed me earlier this year asking if I had any ideas for a workshop. I wrote something like, ‘I have this idea for a writing workshop where we don’t do any writing.’ A big part of Kahini’s kaupapa is connection and diversity and I was excited about the idea that we could experiment with new ways of expressing our work with each other and that there was the possibility that the workshop would attract non-lexical and non-neurotypical authors. With Kahini’s support I was able to design and offer ‘The Writing Workshop Where We Don’t Write’.

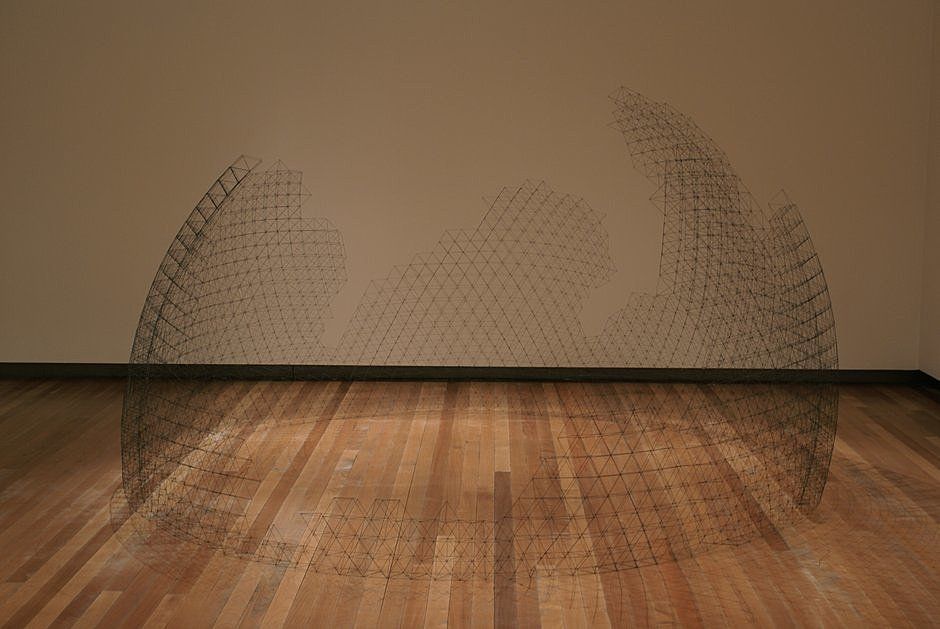

On the first day we translated fairy tales and poetry into colour, sound and texture. On the second day people presented their work and we workshopped it. I suggested that people might want to create, without words, a version of a work that was giving them trouble. We were in a large hall with wood floors and lots of windows. People made their stories and poems in sculpture and taste and sound. One person took us on the journey of her poem from one corner of the hall to the other. I found the experience incredibly emotional. We were often directly accessing senses in a way that was giving us clearer insight to the shape of the work – this part sounds louder than this part, this character tastes metallic here and smells like beer here, when you stand here you can only see this part of the whole story. My impression was that people found answers and questions that were useful. Some people found key images that they wanted to translate directly back into their work. Others gained a new way of looking at the work that seemed to uncover something in it they hadn’t noticed before. There were also new strategies and approaches to the work developed, news ways of ‘coming at’ the work.

This idea of where to approach the work from is an essential part of why my novel houses help me. I think what works for me about the exercise is my position to the work. Where I stand in relation to the novel I’m writing. I often think about what I mean when I say the word ‘structure’. When I’m working with someone on their writing I can identify a structural issue but it always seems quite elusive. It’s not like a spelling mistake or a plot hole, for me, it’s more like a feeling, like there’s something just out of my sight that is undermining what is in front of me. Often I find myself using the word ‘shape’ but I realise now that the structure is not the exterior aspect but rather it’s the under-pinning that gives the work its shape. So, I understand better now why I have to imagine myself inside the work to fully explore what is going wrong or right with the shape I see from the street.

Lynn’s writing about a motorway now. Today I’m writing about the sea. The liquid house I’m wandering doesn’t seem to want walls or a roof, it holds itself up by sheer volume. I’ve just read Ballard’s The Drowned World which always reminds me of how dependant the ocean is on the landscape that holds it. But in itself it isn’t bricks or mortar and in the thing I’m writing, this runny, pelagic building is attached to something solid and tall and worrying. In a months’ time I’ll need to find the access-way from one to the other. But for today I’m wandering the bottom of this ocean, turning over stones, looking up occasionally to see if I can access any light from its surface.

Pip Adam will be running a workshop on structure at The 2016 Kāpiti Writers’ Retreat on the 22–24 January 2016. Details here.