Internet Histories | 10 June

This fortnight: re-mystifying the creative endeavour, the complex complicity of American tech firms, and fluoride - good for teeth, or brain control?

This fortnight:

The re-mystification of creative endeavour | All of the pinks |

Rotting teeth and the disbelief of experts | PRISM |

Libertarians gon' wild

Matt:

Stephen Colbert: The very first sentence of this damn book is, "The internet is among the few things humans have built that they don’t truly understand." Do you understand the internet?

Eric Schmidt: I do not.

—Eric Schmidt on The Colbert Report, April 2013

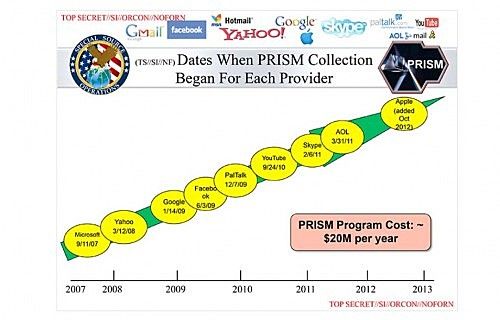

It’s been a shit week to be a large tech company in the United States… or a US citizen, for that matter. It’s looking increasingly likely the US government has been spying on its own citizens by demanding metadata from phone companies (call lengths, cell numbers, that sort of thing) and who knows what else from Apple, Facebook and Google. People in tinfoil hats and hokey (yet compulsive) TV shows have been saying this kind of thing for years, so it seems less shocking than you’d expect. The New York Times said that the Obama administration had “lost all credibility.” A day later, they clarified: “all credibility on this issue.” Thanks, NY Times.

On the upside, if the government is as terrible at surveillance as it is at PowerPoint, there may not be much to worry about. Over the last couple of days, several designers have 'improved' on several of the slides, creating a PRISM brand and integrated graphics.

I redesigned the PRISM PowerPoint slides. Because they were terrible. Now it’s secret government data surveillance — with a smile!™

On the other hand, it’s kind of impressive the US government managed to get anything except devalued shares out of Facebook. For a company used by a billion people, they’re radically opaque. Try sending them an email. You can’t, because they don’t have an email address. Their offices in your country aren’t in the phone book.

Australian channel ABC did a tongue-in-cheek investigation on several companies’ End User Licence Agreements (the things you usually have to “Agree” to every time you install new software). Appropriately, they’re the same companies now attracting PRISM scrutiny. Check it out, from minute 4:50:

*

It looked, at first, like a shapeless pile of floating junk, but as the boat drew closer, a sense of order emerged. The island was made up of two rows of houseboats, anchored about a hundred feet apart, with a smaller cluster of boats and yachts set off to the west. The boats had been bound together with planks, barrels, cleats, and ropes, assembled ad-hoc by someone with at least a rudimentary understanding of knots and anchors. Residents decorated their decks with banners and flags and tied kayaks and inflatable toys off the sides, giving the overall landscape the cephalopodan quality of raver pants. Dirty socks and plastic dishes and iPads and iPhones littered the decks. An enormous sound system blasted dance music, it turned out, at all hours of the day.

I’ve been kind of intrigued by microstates for a long time, and one of their nested subsets is this idea of ‘seasteading.’ Its usual formulation involves a gigantic ship, really a sailing city, plying international waters, free from common law restrictions and government interference. Self-sufficient, they’re a kind of libertarian utopia – a way of escaping the weighty inherited history of the land; part-adventure, part-nomad, part-crazy.

I hadn’t heard of any grand ambitions getting successfully off the ground (or in the water) before reading this story in N+1, about a smaller, more pragmatically-sized colony on a river in California. It reads like someone held up a warped mirror to the hippy communes of the 60s.

I asked Cyprien how he’d ended up so far from home. He explained, in French, that after trying unsuccessfully to obtain an American visa to work as an entrepreneur, he’d won the Green Card lottery and immigrated to the United States about four years ago. He wanted to leave France in part to escape an overbearing state that he found “closed and afraid,” and today sees Seasteading as a potential solution to the lack of competition in government. “There’s no real innovation or genuinely free market in France. I was tired of it,” he said, adding, "Libertarians in the US don’t know how good they have it."

Amen, bruv. Will the persecution of pasty white kids never cease??

James

Earlier this week, the Hamilton City Council voted 7-1 to stop fluoridating their water supply. I’m a scientist, so I think it’s a laughably misinformed decision. I’m not going to re-litigate the arguments for fluoridation, though the bloggers at Sciblogs have done a good job on the Hamilton situation, while the Washington Post has a Brief History of America’s Fluoride Wars. What strikes me about this decision is how low the esteem of scientists seems to have fallen in the media or the general public. Tim Watkin, in a post at Pundit (check the comments if you want to see some of the nutters who seem to think fluoridation is the first step towards putting LSD in the water) sums up some of my feelings well:

There's an odd dynamic going on within our society in terms of our relationship to authority. New Zealanders have long been suspicious of people who tried to tell them how to live their lives - especially politicians and self-declared experts. But there was a reverance for the doctor and, by extension, the scientist. That seems to have been turned on its head.

Frankly, we've got it back to front. We've ascribed self-interest to the most detached and objective group and assumed the biggest self-promoters are the ones to be believed. Is it because we've witnessed the healthy scepticism within science debates and interpreted it as uncertainty or even deviousness? Or have we become so self-helpified that we think we just know better? Are we so wed to 'balance' and 'fairness' that we suspend judgment and give the same credit to the scientist and the pseudo-scientist alike?

As with the sort of people who would rather Ask Jeeves than ask their GP, the ready access to information on the internet seems to reduce, not increase, the collective level of the debate. For every scientist citing a body of peer-reviewed research, there’s an activist who’s found a page on Google and copy-pasted a sentence that supports their prejudice. The media has seen fit to give equal weighting to the opinion of scientists and that of someone who boasts of their lack of knowledge. The Herald’s live chat put Dr Jonathan Broadbent from the University of Otago School of Dentistry up against Mary Byrne from the Fluoride Action Network, who won over the readers with gems like:

there's very good reasons why sea water is not suitable for human consumption. One of them, being there is too much fluoride.

Campbell Live actually boasted about their non-expert’s lack of credentials – “Wendyl Nissen may not be a scientist, a doctor or a dentist – but she’s a mum and she’s one of those people who have done some research.” I’d really like to see this research. Where is it published? Does the Herald peer-review their food columns these days?

I know I’m coming across all wanky and academic at this point, but ‘research’ isn’t just googling things. Much of what you learn in a science degree – and in an arts degrees, or any degree really (commerce excepted) – is not just facts and figures, but the process of discovery. How to perform a literature search, how to refine a question, how to draw conclusions, how to summarise a field in which the data may be contradictory. How to design an experiment. Nissen might have an opinion about fluoridation that I strongly disagree with, but as this quote shows, she also has an opinion on how research is conducted that simply isn’t based in the real world:

There are no studies that say if you have too much fluoride you’ll get X disease, no one’s actually doing those studies, so if I see a study that says its fine I’ll go back to town water but I can’t find one.

I think – if I can parse this garbled rambling correctly - that she is against fluoridation because no-one has yet done a study in which they loaded people up with fluoride until they contracted diseases. I’ll just put this into an ethics application for her:

AIM: To prove that fluoridation of the water supply causes disease in human populations.

HYPOTHESIS: Extremely high doses will cause all sorts of nasty diseases and we will have concrete evidence to show that fluoridation is as bad as chemtrails.

METHOD: Double-blind cohort study. 100 5-year old children separated into a placebo group and a fluoridation group. Administer either placebo or fluoride at increasing doses until all children become sick and / or die.

RESULTS: Positive correlation between increasing correlation of fluoride and death of children. Struck from the medical register, 70-year prison term for medical malpractice and medical manslaughter of 37 children.

It might be a while before Nissen goes back to town water.

The Justice Minister Judith Collins – no great fan of evidence-based policy making when it involves her portfolio, but more than happy to interfere in someone else’s – slammed the Council’s decision as “bollocks.” What was more worrying came later in the story:

Dr Pat Tuohy, chief adviser for child and youth health, said the evidence was "pretty compelling" for fluoride but he reiterated any decisions on the matter were best made by the public.

Hang on - decisions are best made by the public? Why do we even have public health then? Preventative and social medicine isn’t glamourous, it doesn’t inspire TV shows with renegade doctors or nubile nurses. But, dollar-for-dollar, it is the most effective way to reduce disease and illness in the population, and to keep tabs on an ever increasing health budget. Programs such as immunisation, putting folate in bread, and fluoridating water are the most efficient way of reducing incidence, but they do require sacrificing a degree of freedom to the state.

Finally, Kim Hill has been everywhere in the last wee while, but a couple of Saturdays ago she interviewed former Otago Vice-Chancellor Sir David Skegg. He’s been involved in preventative medicine for his entire long, distinguished research career. At one point in the interview, he explains how it can be a counter-intuitive field of research. Kim says she doesn’t understand, and so he goes into detail about individual risk versus population risk - and how reducing the latter is a more effective way of reducing the former. This goes against individual interest – against common sense. As Peter Dunne has shown in the last week, common sense is often wrong, and that’s why decisions like this really should be based on good scientific evidence, and not on common sense. From a piece on Psychology Today:

..common sense isn't real sense, if we define sense as being sound judgement, because relying on experience alone doesn't usually offer enough information to draw reliable conclusions... Real sense can rarely be derived from experience alone because most people's experiences are limited.

Rosabel

I had the great privilege of being part of a panel discussion last week with Judge David Harvey, Troy Rawhiti-Forbes and Russell Brown. In the lead-up to the event we emailed back and forth about the topic – communication, and what it means to live in a real-time world – and one of the topics we discussed at some length, and didn’t get a chance to explore on the night, was the loss of documentation in the digital age. That sounds counter-intuitive given the internet is inherently archival in nature, but while the internet facilitates certain kind of documentation, it removes the need for the existence of others – what of the draft manuscripts and journals of our contemporary novelists, for instance? I’ve spent many an afternoon online poring over the artefacts of creative toll - marginalia, journals, old drafts. What of this now? We’ll have nothing but the final product, with little documentation of the process. In a lot of ways, we’re enabling the re-mystification of creative endeavour.

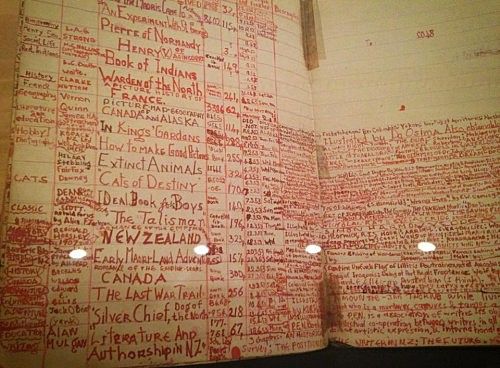

I was reminded of this on Saturday when I was at the art gallery. There’s a glass case in the Tony Fomison collection displaying one of his reading diaries – pictured are the books read in the autumn before he turned 14 (notable: ‘Cats of Destiny’). In an age of automated archival, do we lose the pleasure of a particular kind of insight? The behaviours and thoughts somebody thought was worth cataloguing, and how? And what of mistakes? Embarrassments? Are we editing them from history, too?

As far as documentation goes, though, we also have a lot to gain. This is Hutt Lagoon in Western Australia. Nature's Rothko, and the world's largest microalgae farm. Quite incredibly, these images, taken by Australian photographer Steve Back, haven't been doctored: the lake's high concentration of salt causes the algae to produce beta-carotene in order to protect itself from the sun (beta-carotene is the naturally-occurring red-orange pigment found in fruits and vegetables, like the one from which it was first crystallised - hence its name). Commercially it's used as food colouring, but it also has antioxidant properties and is the precursor to vitamin A, which is important for things like our vision and living.

Then we have the unnatural pinks. The hues that cast the world in a spectacular vibrancy, rendering it alien and new. You might recognise this image - it's from Richard Mosse's project Infra, which documented the conflict in eastern Congo using Kodak Aerochrome film. The film captures infrared light bouncing off vegetation and was, in fact, originally developed for military surveillance during the first World War - but Mosse's tender gaze imbues the scenes with a discomforting beauty.

He has a documentary in the Venice Biennale this year called The Enclave, which is shot entirely on 16mm Aerochrome film.

And who can resist deserts from space (soon we'll have desserts from space too):

[caption id="attachment_6999" align="aligncenter" width="500"] The Egyptian desert: Wild. Celestial. Sinewy.[/caption]